Writers gracing the pinnacle of the mountains of “modernism” have a famously complicated relationship with technology. On the one hand, Eliot’s apparent disdain for the modern apparatuses of the typist’s life, and Heart of Darkness’s eerily discarded rivets like ossified bones come to mind, on the other, the unifying power of the airplane and automobile which travel through Mrs. Dalloway’s early pages.

21st century modernist scholars tend to be less ambiguous about the technological. Digitally, the study of modernism is thriving–something hardly surprising, considering the seemingly irresistible synchronicity of using all the media tools at our disposal to study the first era to offer such a broad multi-media archive (for example, this weekend I discovered that we have access to thousands of hours of recorded city-life sounds from the streets of Manhattan in the late ’20s and early ’30s. This kind of aural documentation is a far cry from historians trying to unearth ancient sounds from shards of pottery or even from EBBA establishing a modern archive of recordings of broadside ballads hundreds of years old).

There is no shortage of collaborations between modernism and the digital humanities to be found on the internet, from single-author or single-work projects like:

to textual and image archives, such as:

to digital collections of critical essays like:

and the blogs of those individual scholars whose work tackles both modernism and digital humanities, including:

There’s even a native Twitter account , which is, in their words, a “simultaneity project: replying Modernism on a 100-year delay.”

Alongside all of these looms yet another resource which is both all and none of these things—The Modernism Lab at Yale University.

Surprisingly, while contemporary academics seem widely aware that the the Modernism Lab exists, a search of the internet reveals nothing even remotely comprehensive in terms of a review or critique of the site, so individual scholars are left to repeatedly puzzle out what’s to be gleaned from this vast archive (I’m tempted to call it a treasure trove!) of information.

Adding to that, the site itself is much more direct about what it isn’t than what it is–The Modernism Lab’s “About” page tells visitors it’s not “a collection of primary documents made available on the web” (like the Modernist Journals Project), and it’s not primarily a source for “authoritative essays on the period” (as they call The Victorian Web).

And what is it? The site claims its “orientation towards ongoing research differentiates this project from other major websites devoted to humanistic research.” Their mission statement goes on to say “As a Laboratory, we hope to pose research questions and work together to answer them.” Heady stuff, but hardly an explicit description of what one might accomplish via the lab’s resources.

The real question those who are drawn to the lab must ask is what can you (or I) do with the Modernism Lab? According to the lab “The main components of the website are an innovative research tool, YNote, containing information on the activities of 24 leading modernist writers during this crucial period [1914-1926] and a wiki consisting of brief interpretive essays on literary works and movements of the period.”

So what I’d like to do today is briefly consider the possibilities (and limitations) of these two features, and when they might (and might not) prove useful to a scholar like me.

First to the Wiki:

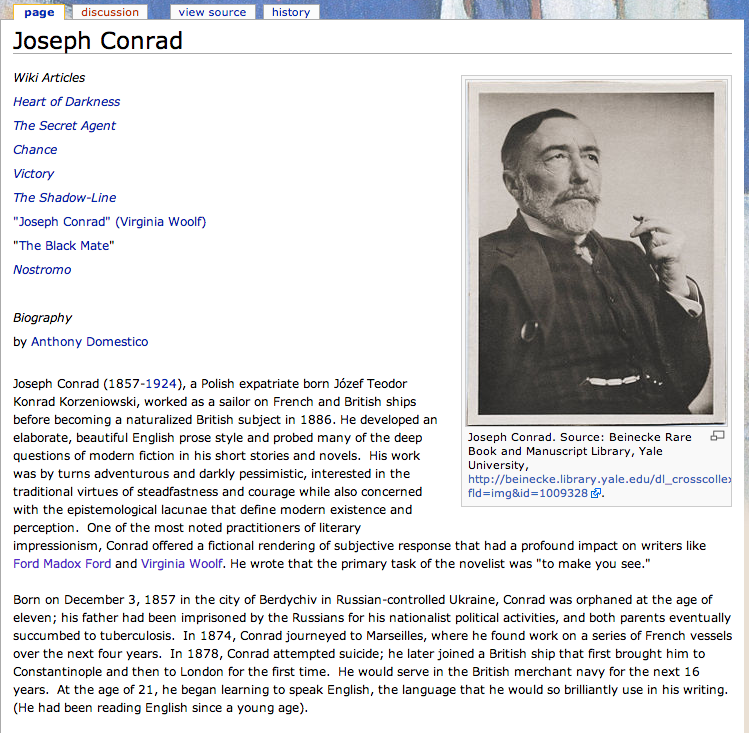

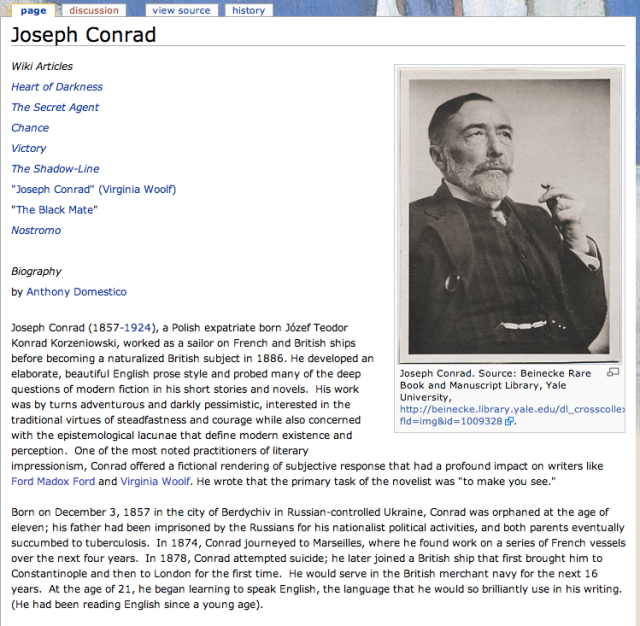

Unlike the YNote side of the site, which claims to only tackle 24 figures (more on that, later), the Wiki provides data on 26 authors from a main page, and an additional 45 classed under “Other Modernist Figures.” The amount of data on each of these figures fluctuates considerably, from a major figure like Joseph Conrad,

for whom, as you can see, there is both a biographical article and subsidiary articles on many of his major works, to a figure like Clive Bell, whose name, it turns out when you click on it, appears in passing in a general piece on Modernist art.

Why these 71 figures were chosen, and why particular works were chosen, for Wiki entries (for example, why is Nostromo absent from the Joseph Conrad Wiki, when both a previous book, Heart of Darkness, and a later book, The Secret Agent, are included?) isn’t a logic revealed to the reader, so searching in the vast corpus can feel rather hit or miss–but when something “hits” it’s pretty exciting!

Within these Wiki entries, the quantity of information to be found varies widely—there’s a long essay on Conrad’s little studied novella The Shadow Line, and a blurb on the much more widely read The Secret Agent (conversely, over at Wikipedia one finds little more than a stub on The Shadow Line, and a lengthy exploration of The Secret Agent, but this attempt to fill in Wikipedia’s gaps doesn’t seem to be a guiding principle for the site, and one easily finds correspondence between the Lab and Wikipedia, such as in the link to the Modernism Lab Wiki on the The Shadow Line Wikipedia page).

The authors of the Wiki entries are all named, so there’s not the familiar Wikipedia doubts about the source to contend with—these facts and analyses come either from the work of graduate students in Yale’s English department, or are adapted from project director Pericles Lewis’ Cambridge Introduction to Modernism. There’s no information provided on whether those unpublished graduate essays have been fact checked before posting, but with the project’s impressive editorial board it’s easy to assume the information is valid.

It seems that, if looking for information via the Wiki, you could easily get very lucky if you happen to be looking for a work or author who is the focus of a longer piece of scholarship (although you run the risk of striking out if the figure in question is elided from this project).

On to YNote, the Lab’s unique, proprietary, feature.

Here’s what the dashboard looks like:

I’ll admit, the first thing that struck me as I began exploring was the question of who is a “Notable Figure” (and why) and who is simply listed under “All People”? This is another decision where the logic is hidden to the user (the Modernism Lab was, in part, designed to accompany and support undergraduate and graduate courses at Yale, and one can imagine that these decisions which are inscrutable to the external user may be explained in the classroom). The “Notable Figures” list turns out to match the Wiki’s 26 main authors, plus Robert Graves, minus Marcel Proust and Franz Kafka—(this is a bit perplexing, as elsewhere on the site it claims to cover only 24 figures–to paraphrase Eliot, “who is the 25th who walks beside you?“).

What YNote allows is really very exciting: The Modernism Lab has indexed biographical and autobiographical works and correspondence archives in order to, in their words, “reconstitute the social and intellectual webs that linked these writers—correspondence, personal acquaintance, reading habits—and their influence on the major works of the period.”

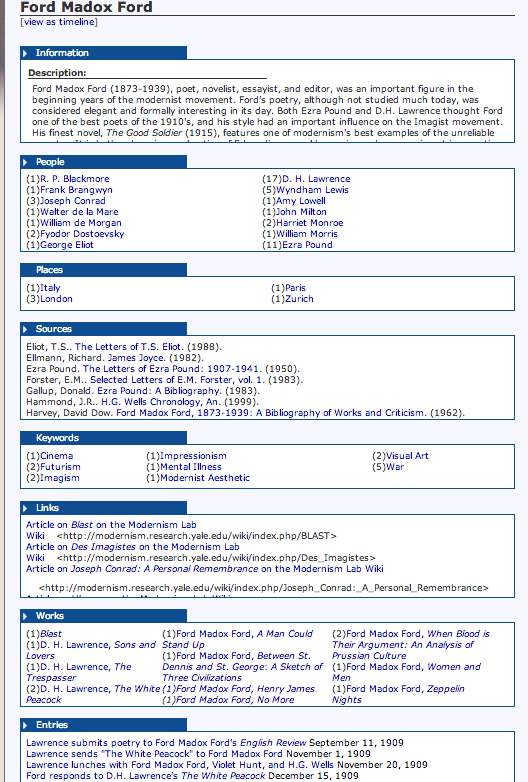

Here’s what’s offered via YNote on a “Notable Figure” (the lab’s turn of phrase, not mine) like Ford Madox Ford:

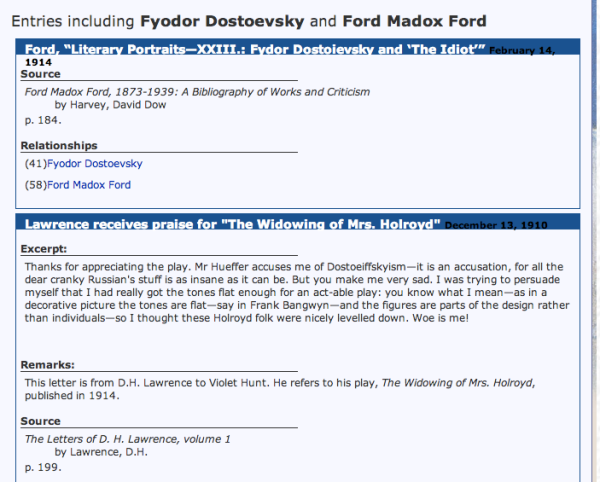

Here one finds those people, places, and movements where Ford’s name turns up in the various documents indexed by the Modernism Lab. Click on “Dostoyevsky” and one finds an excerpt from one of DH Lawrence’s letters in which he says Ford (here named as Hueffer) accused him of “Dostoeiffskyism.”

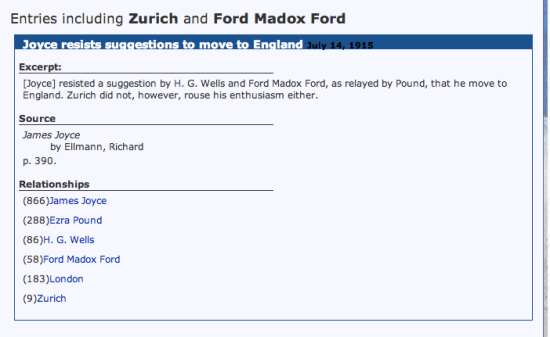

This is a novel way to explore hither-to un-catalogued interactions, but it runs into some problems when you find that sometimes the system is pointing to connections that don’t exactly exist. Clicking on the “Zurich” link, for instance, reveals not a connection between Ford and the city, but rather both those words appearing in the same reported conversation between Ezra Pound and James Joyce.

Also a bit of a mystery is the question of how, even within the temporal boundaries the site limits itself to (1914 to 1926), YNote has arrived at this list of four geographic locales for Ford (Paris, Zurich, London, Italy—3 cities and a country, somewhat perplexingly), and not those parts of England or France where he served in WWI? Some insight into this can be found in which works are listed under the “Sources” tab, but why these particular sources were catalogued and not others remains a mystery to me.

Some Limited Conclusions on Usefulness

If it seems, perhaps, ungenerous to accuse the Modernism Lab of not being comprehensive in its approach when it is most certainly a work in progress and miles beyond anything else available online in terms of an information archive on these figures, consider this simply a wish that there was greater transparency in how decisions of inclusion and exclusion were made, as well as a desire for the bibliography of sources for the entire project to exist in a document easier to navigate than this register: http://modernism.research.yale.edu/ynote/index.php?action=browse&view=9.

I do think that including more details from the outset on what the user can expect out of the site would make it more useful to researchers considering whether to wade into this massive wealth of data.

Besides the lack of transparency regarding the data set, the biggest problem I can point to in the Modernism Lab is that, with the departure of Pericles Lewis for Yale-NUS, the project appears to have stalled (there’s no evidence on the site that it’s been updated since 2012 or earlier).

All of the material and immaterial resources clearly sunk into this project make me eager not to see it abandoned by the wayside–the Modernism Lab is a unique resource for scholars, and, given the ever-growing number of collaborations between modernism and the digital humanities, it seems reasonable to hope that the site finds new leadership and continues to expand its scope and utility.

In the mean time, I’ve got my eyes tuned on another big modernist project in the digital humanities (or digital project in modernist studies?) in the works, from the Maker’s Lab: http://maker.uvic.ca/big/