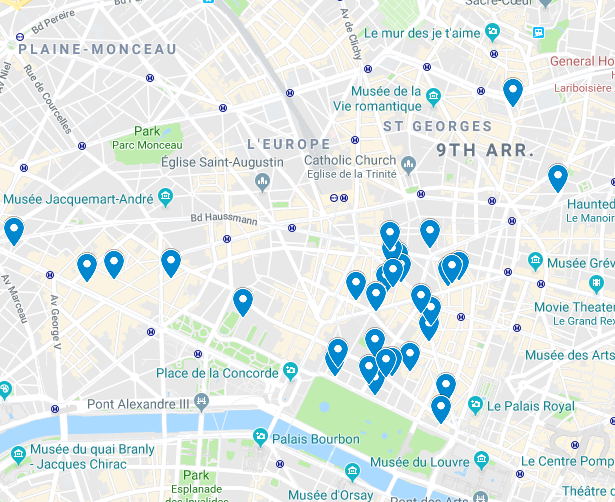

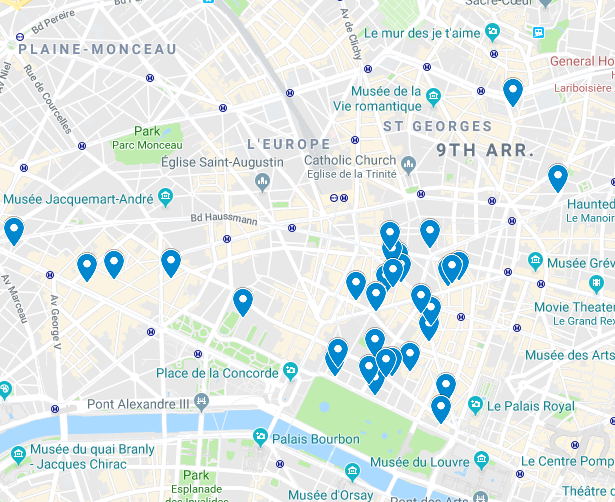

In anticipation of a couple of talks I’m giving this summer, I created a map of all the business advertising to the readers of the American Library in Paris’ little magazine, Ex Libris, in July 1923.

In anticipation of a couple of talks I’m giving this summer, I created a map of all the business advertising to the readers of the American Library in Paris’ little magazine, Ex Libris, in July 1923.

This month, I had the true pleasure of participating in the Modernist Podcast , joining Bret Johnson, Emma West, and host Séan Richardson in a discussion of our work in the archives. You can have a listen here or on iTunes.

It seemed such a pity to discuss archival finds without being able to display them that I’ve collected a few of the pieces I discuss (or just ones I love!) below.

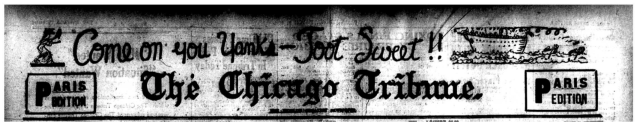

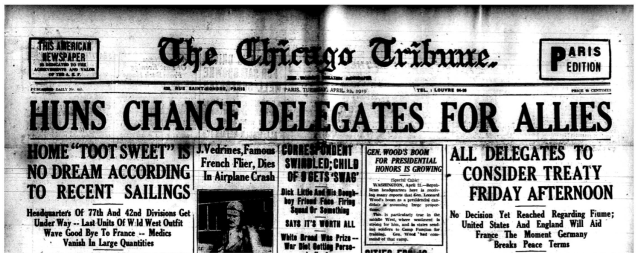

An overview of the “handwritten” messages urging demobilization in the early months of the Chicago Tribune Paris Edition’s publication.

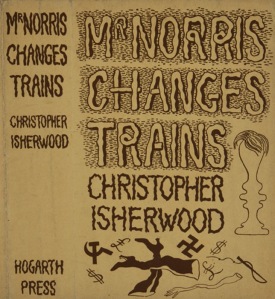

By some coincidence, this past week my syllabus included plans to discuss the Nazis’ rise in Weimer Germany with my students. It’s an Intro to Literary Studies class, and this week’s critical lens was historicism.

We were reading Christopher Ishwerood’s Mr. Norris Changes Trains—set in the early 1930s, its events culminating in the Reichstag Fire and violent force used against the Nazis’ communist opposition. The book was published in 1935—WWII’s atrocities had yet to occur—but by book’s end there are premonitions of the cleansing that is to come.

I planned to argue to them that the narrator, William Bradshaw’s, constant misreading of situations, his unreliability, stands in for the German people’s lack of awareness of what they’re allowing to rise to power. That all the ways the book withholds knowledge from readers echo this theme. I planned for us to to discuss whether ignorance makes people complicit.

And then, as I worked on the week’s lessons, Charlottesville happened, and the relationship between obliviousness and complicity felt anything but academic. But what to say and how? 1933 and 2017 felt uncomfortably close—their overlaps almost too obvious to point out.

I was heartened to find on Monday that the class all claimed some knowledge of what had happened over the weekend. But I still wasn’t quite sure how to incorporate Charlottesville into our discussion. I teach at a public university in California, my students are largely Californians, from a broad spectrum of backgrounds, so I can count on most of them sharing a common political perspective (and being fairly used to educators who don’t refrain from sharing their own politics).

And we did discuss Weimer Germany, with the help of this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kybjUg4kw_s

And we watched a few minutes of this to know what Nazis believed in: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvCkw87FLZk

And after a full class session discussing the 1930s, and the history and politics explicit in Mr. Norris I felt ready to show them this:

I knew this was disturbing enough to shut conversation down (I cried at its opening shots when I first watched it), so we followed it with a little bit of catharsis in the form of superheroes punching nazis: http://www.cbr.com/punch-a-nazi-15-times-superheroes-fought-fascism/

(I like to think I never condone violence, but was forced to make an exception). Then we had a 5 minute break, before coming back to resume conversation.

And the reaction was perfect—students immediately articulated obvious connections between the 1930s and the 2010s, they talked about the racism and white privilege they’ve witnessed and experienced in their own lives, and they brought it back to the book to discuss the places where the novel and the narrator’s facades of cluelessness crack, to reveal deeper understandings of truths about both politics and human nature.

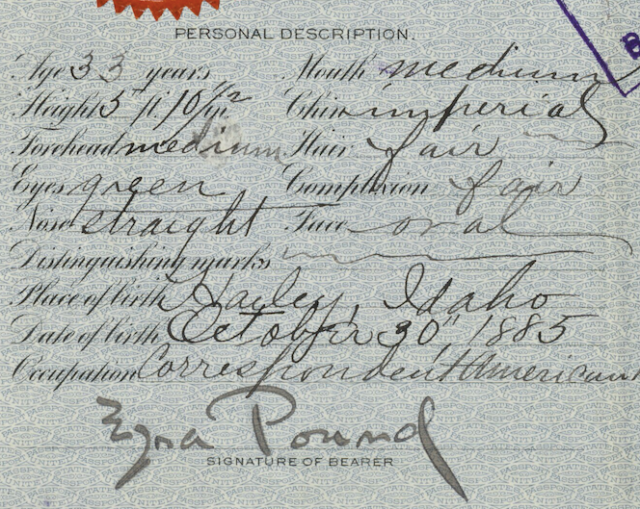

Spent the morning attempting to create a written description of Ezra Pound’s 1919 passport. When you see how many consulate visits it took to gain permission to travel from the UK to Italy in 1920 (American, French, Swiss, and Italian) it’s no wonder he wrote in to The New Age railing against the passport, complaining “let us have one photo printed on the right shoulder…another deposited in each of the main rogues’ galleries in Europe.”

Anyways, the best bit of Pound’s passport comes in the “Personal Description” section (despite the passport photo’s introduction around the start of WWI, American passports included physical descriptions of their bearers until about 1925). I’ve had a long running obsession with the description of things like forehead and mouth as “medium,” but am pretty sure this description of Pound’s chin as “imperial” is my new favorite adjectival critique.

Ready to write a treatise on Pound, empire, and the implications of the chin being the imperial feature, I went to the OED to find out if there was some meaning of “imperial” I was missing. Of course, there was: Definition 8, “A small pointed beard growing beneath the lower lip.” There’s much to be made, I suppose, of the fact that Pound sported a style known as imperial, and that “chin” and “beard” are interchangeable in a physical description, but less to say about colonial physiognomy than there might have been.

Excited to be a speaker at a UCSB “Lunch and Learn” next week, showing off some of the oddities of the Chicago Tribune Paris Edition, like this fake handwriting over the title:

Despite origins dating at least to newspapers published for British citizens in colonial America, the global repercussions of media targeting national audiences beyond national borders remain substantially unexplored. Unanswered are the questions of what repercussions expatriate media has on global citizenship; whether these publications facilitate adhesion to a parochial national identity, despite distance, or create a new form of national belonging; and how newspapers establish narratives of cultural and political coherence abroad. Papers welcome on texts or news sources from any medium or period that connect immigrant or expatriate communities to their homeland. For example, colonial gazettes, interwar dailies, or contemporary broadcast media for emigrants. Please send 300-word abstracts by 10 March 2017 to Nissa Cannon (ncannon@umail.ucsb.edu).

I had so much fun talking about Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” today with my students that I thought I’d post my lesson plan.

We started with this fun recap of Thoreau’s ideas, from the classroom-pleasing School of Life.

With that in mind, I assigned each student three pages of “Civil Disobedience” to comb through for pithy statements and witty comebacks in the text that might be equally applicable in today’s political climate as in Thoreau’s.

Then, the game got started: “What Would Thoreau Do?” (or, really, say):

Students were asked to respond to current news clips with quotes from their assigned pages of Thoreau’s text.

Because I couldn’t bear to subject myself, or my students, to the White House’s actual press conferences, we got our news from the late shows:

Steven Colbert on the refugee ban and Steve Bannon, and Samantha Bee on Sally Yates and the appointment of campaign donors to the government.

Pausing after each topic for Thoreauvian responses, we laughed, we (nearly) cried, and even some of my quietest students were up to the task of embodying Thoreau.

Just back from the Modernist Studies Association’s annual conference, and still buzzing with conference energy while trying to squeeze everything I have to into this short Thanksgiving week.

MSA was, as always, such a joy–met new people, saw brilliant work presented, had new ideas for my current work and future projects.

I was speaking on a panel called “Modernist Cultures of Information,” and I’ll leave you a brief abstract here to whet your appetite:

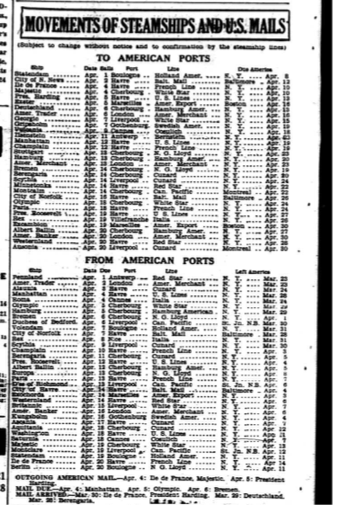

“Via archival research on the largely un-examined Paris Tribune, my paper charts the evolution of the newspaper’s arrivals and departures listings, from the paper’s early days as the Army Edition of the Chicago Tribune in 1919, through its closure, a victim of the Great Depression, in 1934. What began as simply a list of boat names and departure dates, presuming prior knowledge of shipping lines and voyage lengths, evolved into an informative table conveying a wealth of information, with several incarnations along the way. The evolving nature of this daily chart reveals an effort to balance lengthy headnotes explaining the data with information that could be parsed at a glance by a reader, revealing increasing attention to methods of presenting information clearly and concisely. I scrutinize this shifting data-set to speculate on the changing assumptions of the reader’s knowledge and needs, examining the ways the column’s evolution mirrors the shifting audiences the paper catered to.”

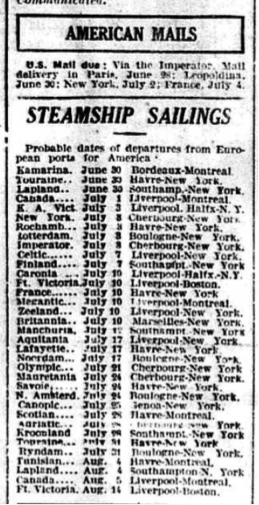

Or, in visual terms, how the steamship column transformed from this:

To this:

More on this soon? I hope so!

I’ll admit, I’m pretty excited about this panel I put together for PAMLA:

Permanent Ephemera: Travel Documents and Literature

Papers on Audubon, Dracula, and Hemingway.

Stay tuned for a re-cap of our conversation after next weekend’s conference.